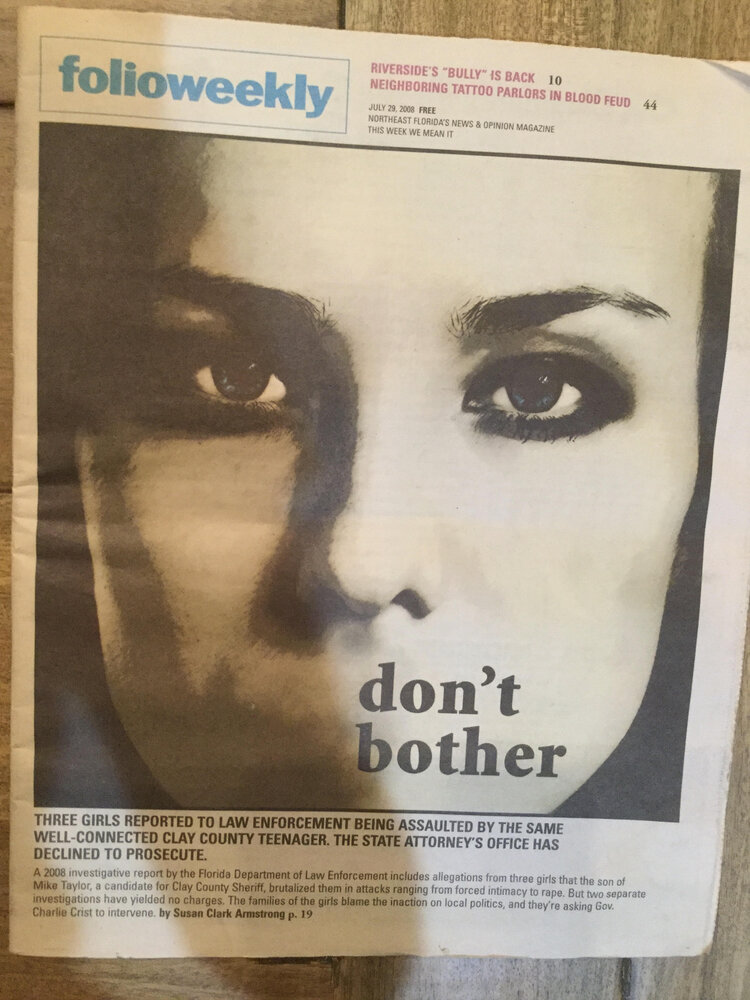

Two girls say they were sexually assaulted by the same well-connected Clay County teenager. The State Attorney’s Office has declined to prosecute.

By: Susan Clark Armstrong Folio Weekly

* The names of the victims, their family members and some witnesses have been changed.

“Life changed in an instant.”

Seated in her brightly lit family room, just a few feet from her youngest child, Katherine Jones* describes the sudden transformation of her daughter Brooke*. “My naïve, happy, open and self-confident child — who loved school — turned angry, moody, tearful,” she recalls. The then-14-year-old girl vacillated between being unapproachable and clingy, says her mom. “I had to force her to go to school.”

Katherine didn’t yet know what had happened to her child. But she says she often found the teen roaming their Fleming Island house late at night, peering out the curtained windows. The girl was uncharacteristically quiet and withdrawn, no longer part of the loud and spirited nattering among her three older siblings. Brooke’s parents were worried, but the girl insisted nothing was wrong. When Katherine finally did learn what was wrong, several months later, she was almost as shocked by her daughter’s long silence as the actual news: Brooke had been violently sexually attacked.

In fact, Brooke’s silence was in keeping with what law enforcement professionals say is standard practice for teen victims of sexual assault. According the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, only 6 percent of teenage victims of rape or attempted rape report it to police. Seventy-eight percent don’t tell their parents.

Given the outcome of Brooke’s own case, her silence is not surprising. She, along with two other Clay County girls, attested to violent encounters, ranging from forced intimacy to rape, with the same teenage boy. A Feb. 27, 2008, investigative report by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement obtained by Folio Weekly includes allegations from three girls that Adam Taylor, now 19, attacked them. The girls didn’t immediately report the crimes because they were afraid. Part of their fear stemmed from the fact that Adam Taylor is unusually well-connected in the law enforcement world. His dad, a veteran law enforcement officer who spent more than nine years with FDLE, is currently running for Clay County Sheriff. (Neither Adam Taylor nor his father, Mike Taylor, returned numerous calls for comment.)

The girls also expressed fear that Adam would come after them. But mostly they worried their stories would not be believed, or that they would somehow be faulted for the attacks. That fear was well-founded. In two separate investigations, the State Attorney’s Office declined to charge Adam Taylor. Prosecutors cited such things as the lack of witnesses or inconsistencies in the girls’ stories as reasons not to prosecute. In one case, they cited the victim’s alleged promiscuity as a reason, even though Florida law is clear that “prior sexual conduct is not a relevant issue in a prosecution.” In another, police cited the girl’s subsequent decision to ride in a car with her attacker as reason to doubt her credibility. According to rape crisis counselors, both reasons fail to consider how young girls respond to rape and how the state must work – sometimes very hard – to ensure that attackers are brought to justice.

For the parents of the girls, the excuses are just proof of how the system failed their daughters. They recently sent a letter to Charlie Crist, imploring the governor to reopen the case. Given the severe psychological impact of the attacks, they say they may also seek a civil remedy.

“A crime has been committed,” the families wrote in their letter to Crist. “We sincerely pray that you will help right this atrocious injustice.”

Brooke Jones* sits on a chair in the family room, her gangly frame folded into a tight ball. She has dark circles under her eyes and makes little eye contact. Earnestly examining the blunt ends of her short blond hair, she begins to tell her story.

On Feb. 24, 2006, when she was just 14 years old, Brooke joined her slightly older sister, Amy*, in bringing cake and balloons to their neighbor Lindsay’s house to celebrate the girl’s birthday. After the party, they joined a longtime family friend, Ryan, at the community pool, then headed to his friend Chase’s house. There, they met up with several other teens listening to music and playing computer games. Chase’s parents weren’t home.

As Brooke sat watching some kids play games, Lindsay approached her and told her one of the teen boys “wanted to talk to” her. She pointed toward a door off the family room. The teen Lindsay referred to was a sophomore at Fleming Island High School, and although Brooke knew who he was, she says she’d never interacted with or even “thought anything” about him.

The room was dark as she entered, and Brooke hesitated. At that moment, she says, her attacker stepped out of the closet and slammed the bedroom door. Brooke says he pushed her on the bed and began roughly touching her breast as he started to unbuckle his belt. “I kept telling him to stop, that I liked another boy,” she says, her voice beginning to crack. “He started biting my neck really hard.”

Brooke attempted to push him away, but says her attacker then “bit” her lip. “So I smacked him hard on his face.”

“You shouldn’t have done that” Brooke says he growled. “Then he did something to me,” she says, fighting back tears and beseeching her mom to finish the account.

“He clenched his fist and rammed it hard into her vaginal area,” says Katherine with a forced calm. “Then he rammed his fingers inside her.”

Brooke says the pain was intense; she screamed and began to cry. Moments later, she says, Ryan broke the door open. She remembers other teenagers standing by the door asking, “What happened?” Brooke’s sister Amy took her into the master bathroom. Ryan went for ice for her neck. Brooke told her sister what had occurred, and saw she was bleeding. Amy called their mother and told her to come pick them up immediately.

Several supplemental reports generated by the Clay County Sheriff’s Office between July 2006 and August 2006, as well as a Draft Investigative Summary by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement dated April 10, 2008, identify Brooke’s alleged attacker as Adam Taylor. According to the reports, Adam, then 16, acknowledged he asked Lindsay to summon Brooke into the bedroom. He admitted he “fingered” her, but that is where the stories diverge. Taylor said he could tell Brooke wanted to “make out” with him because they had flirted at school. He said the girl came into the room smiling, so he took off his shirt and unbuttoned his pants. He said he put his fingers inside her panties, then stuck his fingers inside her vagina. Taylor said Brooke told him she liked another guy in Orange Park, so he stopped. He said everything that happened inside the room was consensual.

Adam said that Ryan then opened the door and Brooke walked out. He said when she noticed a big “hickey on her neck,” she “freaked out.”

According to the FDLE Investigative Summary, the teens who were present when the incident occurred were reluctant to discuss it. Several parents refused to allow their children to give statements to police. The stories that officers did obtain varied in some particulars. For instance, Brooke’s sister Amy said that Ryan had forced open the door after they’d heard something like a scream from inside the bedroom. Ryan himself offered only a vague explanation of why he entered the room so dramatically, and did not say he heard a scream. According to Ryan’s statement to Clay County Sheriff’s Office, Ryan asserted, “the lights in the bedroom were off and it was dark inside the room. He stated that Adam hurried to the door and tried to block him from coming in, but he pushed Adam back away from the doorway and went in anyway. He stated that Adam was not wearing a shirt, his belt buckle was dangling and he was out of breath.”

Others noted that the music was loud, the atmosphere somewhat confused. Jordan Herrington, Adam Taylor’s best friend, told investigators he didn’t hear anything before the door was opened, but agreed that Brooke was crying when she came out, and had a large, red hickey on her neck. In his recollection, he asked Taylor what had happened, and Taylor replied that “she didn’t want it” because she liked someone else.

Ryan also recalled asking Adam Taylor what was going on. According to a Clay County Sheriff’s Office incident report, he said Adam replied, “I was trying to get some.”

Katherine first learned of the attack not from Brooke or Amy, but from her oldest daughter, Susan, in whom Brooke eventually confided.

Katherine was devastated by the news. Her instinct was to report the crime immediately, but she was also wary. “We had heard Adam’s dad was a policeman, but we didn’t know where,” she says. “So as soon as we found out about the attack, the last of June or early July, we went to the State Attorney’s Office instead of the Clay County Sheriff’s Office.”

The State Attorney’s Office referred them to the Clay County Sheriff’s Office’s Internal Affairs Division and Sgt. Ken Wagner, who was “kind and helpful,” Katherine says. He took their information and told them an officer would contact the family. He also assured them that Adam Taylor’s dad didn’t work for the Sheriff’s Office.

In early July, Det. Charles Sharman was assigned the case. Katherine was relieved when he said he didn’t know Adam Taylor’s dad, and notes that the detective was initially professional and sympathetic. She asked him to interview the kids from the party before Adam, so Adam wouldn’t have an opportunity to influence them, and he said he would.

Sharman’s manner was quite different by their next conversation. Katherine recalls he seemed cold and distant, and he repeatedly mentioned that he had talked to “Mike” about the case. When she finally asked, “Who’s Mike?” Sharman answered, “Mike Taylor – Adam’s dad.”

Katherine was floored. “Why would you do that?” she demanded of the detective. “Why would you talk to the father of the boy who hurt my daughter?”

Sharman explained that Mike Taylor was an officer with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and would “get the details anyway.”

Word was certainly getting around. Katherine’s older children told her that Brooke’s allegations were the buzz at community pools, parties and hangouts on Fleming Island. Brooke entered counseling, but as summer wound down, she became fearful of what she would face upon returning to Fleming Island High School. The prospect of seeing her attacker daily was too much for her. She asked to transfer to Orange Park High School, and her parents agreed. She met with Sam Ward, then principal of Fleming Island High, and told him what had occurred with Adam Taylor. Although Folio Weekly was unable to obtain any records from that meeting, Ward signed off on the transfer.

Brooke’s parents were eager for news in the case, but say Sharman became increasingly uncommunicative. They had to call the detective numerous times to get him to return a single call. When he did call, they say, he always mentioned Adam Taylor’s dad, now referring to him as “Mikey.”

“It felt like a warning,” Katherine admits. “But, foolishly, we still felt justice was possible.”

By late August, Sharman had stopped returning the family’s phone calls altogether. In early September, Katherine contacted Sgt. Wagner and asked him to check on the progress of their case. He reported back that the State Attorney’s Office had decided not to prosecute.

“Sharman didn’t even have the common decency to call us,” says Katherine.

The case was “exceptionally cleared,” meaning no charges were filed, even though there was enough evidence to warrant an arrest. This sometimes occurs when a victim refuses to press charges, or if a juvenile is released to his parents instead of being charged. In this case, officers with the Clay County Sheriff’s Office told Folio Weekly it just meant the State Attorney’s Office decided not to prosecute, possibly because of difficulties the case presented.

Sharman’s final report, dated Sept. 12, 2006, reads:

“Certain facts in this case significantly hinder the successful prosecution of the suspect and those facts are as follows:

1. The victim delayed reporting the sexual battery for five months.

2. There is no physical evidence due to the delayed reporting of the incident.

3. The victim’s sister corroborated her story, but four independent witnesses that were in the residence at the time of the incident did not corroborate her story.

4. The suspect admitted to putting his finger in the victim’s vagina, but said it was consensual. He stated that they were in the bedroom “making out” and he stopped when she told him that she did not want to have sex because she likes another boy in Orange Park.”

Sharman did not include in his list a troubling allegation made by Adam Taylor and his best friend Jordan Herrington, though it did appear in the final report. Both boys said that a few weeks after the alleged attack, Brooke and her sister Amy accepted a ride to the beach from Adam, and later removed their bathing suit tops for him and Jordan. The girls denied the incident. According to their subsequent statements to FDLE, they had planned a beach outing with Ryan and were waiting for him to pick them up after school when Adam pulled up. Adam told the girls Ryan had sent him to get them and bring them back to Ryan’s house. Brooke’s sister Amy told investigators Brooke was “very reluctant” to get in the car, but added that the time at which students were required to be off campus was approaching “and they had no other ride.” Amy told Folio Weekly that she pulled her sister into the backseat of the car, worried they’d be stranded. Besides, she reasoned, Ryan’s house “was only a mile from school.”

The girls say Adam never took them to Ryan’s house, instead driving them to Jordan’s house in Baldwin, then down to a remote beach near St. Augustine, and back again to Jacksonville. At one point, he got a flat tire. Katherine told Folio Weekly that Brooke called her crying three times, the first time begging her mother to come and get her.

Katherine recalls the day well, and says, “I get sick every time I think of that day,” but adds she had no idea of the magnitude of what was happening. She says that Brooke had been extremely weepy in those weeks anyway — which is why she’d thought a beach trip would be a good outing for her. She also says that neither she nor the girls had any idea where they were, and she assumed the girls would get home long before she could find them. She also didn’t know what had happened between her daughter and Adam, and she assumed the girls would get home long before she could find them. When they called a third time, Katherine recalls, Adam was lost, and she had to direct him home from downtown Jacksonville.

The girls categorically deny that they ever took off their tops for the boys or did anything besides ride around with them. But Sharman noted the beach outing in his report, and in conversations with Folio Weekly, several officers with the Clay County Sheriff’s Office pointed to the incident as proof that Brooke’s story wasn’t credible. “Victims don’t get in a car with someone who attacked them,” commented one.

It’s a legitimate point, one which Folio Weekly asked both Brooke and Amy about at length. In the end, their mother may offer the best explanation: “She’s 14 years old. How many 14-year-olds do you know that have perfect judgment?”

In fact, the girl’s behavior may not be as inexplicable as it first appears. According to Psychologist James Vallely, part of the Child Protection Team for the Rape Crisis Center of Jacksonville, rape victims – particularly young ones – often put themselves back in harm’s way with their assailants, and many are re-victimized. Because her sister was there, he adds, Brooke may have felt safer. But the fact that she showed a “fear response,” he says, “in fact enforces her contention that she was attacked.”

Ultimately, Vallely says that for law enforcement to discount Brooke’s allegations because of her subsequent behavior is “totally absurd … We know from years of research that a victim will act in nontraditional ways after an attack.”

Sharman’s report concluded, “Assistant State Attorney Samuel Garrison stated that there are sufficient facts to support an arrest of the suspect in this case. However, due to the above listed reasons, the probabilities of successful prosecution are minimal. Therefore, the prosecutorial merit of the case is such that charges will not be pursued.

” The case was “exceptionally cleared.”

Daniel Cannon* remembers the promise he made to God when his daughter Samantha was born: “I would always protect her and take care of her.”

A lot of the work of protecting and caring for his daughters fell to Daniel. His wife, Jill, works 9-to-5, and because his full-time job is flexible, he has served as their primary caregiver for most of their lives.

Pictures of Samantha’s Sweet 16 birthday party in March 2007 show a petite, pretty girl with long blonde hair and bangs that frame her blue eyes. She looks closer to 12 than 16. She looks happy.

Just a few days after the pictures were taken, however, life for Samantha changed dramatically. Her father and mother would come to barely recognize the smiling teenager in the photographs.

According to her parents, over a period of days, Samantha became sad, secretive and argumentative. Over the following few weeks, her grades plummeted. Her longtime friends were replaced by a group of obviously “troubled” teens, and she seemed filled with self-loathing. Her MySpace page, which her parents monitored, reflected this change. The once self-confident, smiling girl now posted dark ramblings and referred to herself as “dumb,” “stupid” and a “skank.”

The girl’s parents placed her in counseling, but things didn’t improve. The counselor confirmed that their daughter was suffering from depression, but offered no explanation about the cause or why she had changed so suddenly.

Brooke’s sister, Amy, was the first to find out. She knew Samantha only vaguely from school, but says the girl approached her at the Fleming Island Walmart during the Christmas holidays of 2007. She asked Amy what had happened to the boy who attacked her sister.

“Nothing,” Amy spat.

Samantha stammered a reply: “He raped me.” Hesitantly, she told Amy her story. She said she’d been sexually assaulted by the same boy who attacked Brooke. She added that she knew of another girl whom the boy had raped, and still another that he’d “gotten rough” with. Samantha didn’t want anyone to know about her own experience, but Amy immediately told her mother.

Shortly after Christmas, in early January 2008, Katherine Jones contacted Sgt. Wagner and told him the girl’s story. A report generated by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement identifies Samantha’s attacker as Adam Taylor.

According to Katherine, Wagner explained that Adam Taylor’s dad was now running for Clay County Sheriff. Given the potential political implications, he said it would be best if the case were turned over to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Because Mike Taylor had worked in FDLE’s Jacksonville office for nine-and-a-half years, they referred the matter to FDLE headquarters in Tallahassee. They, in turn, passed it along to the executive branch of FDLE, controlled by Gov. Charlie Crist.

On Feb. 13, FDLE called Samantha. She agreed to be interviewed later that day at Fleming Island High School. According to FDLE’s investigative report completed April 10, Samantha and her close friend, Iris, were at her house in late March or early April, 2007, when she got a text message from Adam Taylor. Samantha told investigators she’d been friends with Adam’s younger brother for some time, and had met Adam through a mutual friend some weeks earlier, but had never dated or been intimate with him.

According to Samantha’s statement to FDLE, Adam asked if he and his friend Bud Knight could come over and “hang out,” and Samantha agreed. In his statement to FDLE, Bud said Adam told him on the way to Samantha’s house that he was going “so he could have sex with” her.

When the boys arrived, Samantha invited them in. All four went upstairs to Samantha’s room where the boys watched TV and the girls folded laundry. According to the FDLE report, after a while, Iris, Bud and Adam went to get something to eat. (Bud told FDLE that, in fact, “Taylor indicated that he and [Samantha] wanted some privacy.”) The three headed downstairs, but a few moments later, Samantha told FDLE, Adam returned to the bedroom, locked the door and pushed Samantha down on the bed. He yanked her pants down, but she immediately pulled them back up. Adam pulled off his own pants and boxers, then pulled her pants off again. He held her down and raped her. According to the report, Samantha “continued to say ‘no’ as Adam Taylor responded ‘yes.’” The girl told investigators that she tried to scream, but he covered her mouth. When he was done, Samantha told investigators he pulled his pants up and warned her, “Don’t tell anyone about this.”

Samantha said she screamed at him to get out of her house. He did: He walked out of the bedroom, down the stairs, and left with his friend. Bud told investigators that Adam had gotten what he’d come for: “sex.”

Samantha came downstairs a few moments later and told her friend what had happened. Iris confirmed the story to investigators, along with an incident that occurred shortly after the teens left. A few minutes after the boys left, Samantha’s phone rang. The caller ID read, Adam Taylor.

According to the FDLE report, “[Iris] advised that [Samantha] handed her the telephone and stated she did not want to talk to him. [Iris] stated that she answered the telephone only to hear Adam Taylor state, ‘Don’t tell anyone what happened.’”

Samantha and her friend did keep the incident a secret. Partly, they were afraid of what Adam might do. Iris told investigators “the reason she never told anyone about the incident was because she was ‘afraid’ that Taylor might come back for her.” But Samantha was worried about something else, too. “My dad always said he would kill anyone who hurt me,” Samantha says in a low voice. “I knew he would do it, too, then he’d go to jail. I love my dad, and I couldn’t do that to him.”

The February morning that Samantha told her story to investigators, she called her father to see if he was at work. Given his daughter’s behavior over the previous 10 months, Daniel Cannon became suspicious. He left work and drove to his daughter’s part-time job. She wasn’t there, so he called her. She explained that she’d had to leave work to be interviewed by an investigator from FDLE, but wouldn’t tell him why. Daniel contacted FDLE himself. The news the FDLE agent gave Daniel made him physically ill. His first thoughts were of his daughter’s welfare. His next thoughts were of killing Adam Taylor.

“I was supposed to keep her safe,” he says, trembling with anger. “That animal came into my home and did this terrible thing to my little girl. And I wasn’t there to protect her. Now she sleeps in the same place he attacked her.”

Daniel’s outrage doesn’t stop there. He believes that the crime against his daughter was part of a pattern of behavior by Adam Taylor, and ultimately avoidable. “If Officer Sharman had just done his job,” he adds, referring to the Brooke Jones investigation, “this terrible tragedy would not have happened to another girl.”

In the course of their investigation of Samantha’s case, FDLE spoke to one other girl who attested to a forced sexual encounter with Taylor. According to the girl’s interview with FDLE, Taylor asked her to a car show in Jacksonville. She agreed, he picked her up in a car with two other boys — Jordan Herrington and a teen she didn’t know. The girl told investigators she rode in the back seat with Adam. At one point, the girl said Adam instructed Jordan to pull over. When Jordan asked why, Adam replied, “Just do it.” When the car stopped, the girl told investigators that Adam began kissing her and grabbing her. She pushed him away, but he persisted, telling her to “chill out” and saying, “don’t worry about it.” She fought back, pushing him away and telling him “no” and “stop.”

Eventually, the girl said, Jordan said, “Let’s just go,” to which Adam replied, “Fine.” They took off driving, and Adam moved back to his own side of the car. The girl said no one spoke the rest of the drive, and the teens took her straight home. Despite her statement to FDLE, when contacted by Folio Weekly, the girl flatly denied the incident ever happened.

A fourth girl, who told several individuals that she’d been raped by Adam Taylor, confirmed the story when contacted by Folio Weekly. However, the girl said she would deny the story if contacted by police. She said she couldn’t let her parents know about it – “it would kill my parents” – and she knew if she spoke to police, her parents would find out.

In the course of researching this story, Folio Weekly requested and reviewed many criminal and non-criminal records relating to Adam Taylor. However, on June 25, 2008, the teen’s attorney Mark Sieron notified the State Attorney’s Office that such records should be kept private. Noting that “this investigation involved conduct that allegedly occurred only while Adam Taylor was a juvenile,” the attorney asserted that the files weren’t public records.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement and the State Attorney’s Office both declined to release additional records after receiving the attorney’s letter. However, documents acquired before the decision, including incident reports from the Clay County Sheriff’s Office and information from the State Attorney’s Office, detail Adam Taylor’s many experiences with the legal system – both as alleged perpetrator and alleged victim.

Adam’s name first surfaced in law enforcement circles in May 2002, when he was 11 years old. The report, according to the records department of the State Attorney’s Office, shows that he was charged with “battery.” Folio Weekly contacted his victim, who confirmed the incident, but declined to discuss it on the record. Since Taylor was a juvenile, no details or disposition of the case were available.

Subsequent records from the Clay County Sheriff’s Office show that Adam Taylor ran away from home at least three times; a statement from his mother suggests it was more. The agency also has a case from December 2005 in which Adam Taylor accused his father of child abuse. The case originated with a call to the state Department of Children and Families’ abuse hotline from a borrowed Orange Park cell phone. A county deputy was dispatched to Orange Park High School, where he interviewed Adam. The teen said he’d returned home after running away, and that his father hit him in the face and knocked him down in the bathtub. He said when he attempted to flee, his father intercepted him in the foyer of their home and “body-slammed” him to the floor.

The officer noted a “swollen and bruised” area on Adam’s upper right cheek and said the teen also complained of tenderness on the back of his head and on his back.

Mike Taylor agreed to give a statement to police with his attorney, Hank Coxe, present. In his statement, Mike Taylor explained that he had picked up his son, who had run away on Dec. 3, 2005, and took him back home. The elder Taylor said that he cuts his children’s hair as a disciplinary measure, so he ordered Adam to the bathroom. There, Adam still displayed “a severe attitude” and gave his father a “thousand-yard stare.” The elder Taylor stated that his son “clenched his fist and jaw and came off of the tub.” Taylor said he struck the boy in “an openedhanded fashion,” and when the boy tried to run away, he chased him and tackled him to the ground. Adam Taylor subsequently recanted his story, and the case was labeled “unfounded.”

On May 11, 2006, according to a Clay County Sheriff’s Office incident report, Taylor instigated two fights in one day with a fellow high school student whom he believed had stolen money from his brother. The student denied stealing the money. Witnesses said both fights were violent and several students caught them on their cell phone recorders. The case was also “exceptionally cleared.”

On April 23, 2007, according to the FDLE investigation, Adam Taylor was involved in another fight, this one with Bud Knight (the same teen who accompanied him to Samantha’s house). According to Bud’s mother, Lisa, the two boys were once good friends. Adam routinely spent the night, and they hung out after school. But a misunderstanding over a girl led to a violent conflict in the front yard of Lisa’s house. Witnesses contacted by Folio Weekly said it wasn’t much of a fight—that Adam simply got Bud in a headlock and pummeled him. But the outcome was plain: Bud was missing a front tooth, and his shirt was covered in blood. (His mother saved the shirt, grisly proof of the crime.)

Lisa was determined to press charges, but says that Adam Taylor’s father urged her not to. She says Mike Taylor pointed out that Bud was already on probation for a marijuana charge, and that he could go to jail if he was found to have participated in the altercation. He said if she dropped the charges, he would pay her son’s dental bills up to $2,000.

In the end, Lisa told Folio Weekly, the money didn’t come close to paying for Bud’s $10,000 worth of dental work, including failed bone grafts to repair his missing tooth. But Lisa says the elder Taylor was very convincing. “He was a police officer,” she offers. Besides, she was scared for her son, and as a single mother, she had no idea how she was going to pay for her son’s dental bills. She agreed to drop the charges.

As a “show of good faith,” the senior Taylor said he would bring Lisa a down payment. To her surprise, he also brought a document for her to sign. The paper “completely releases and forever discharges the Defendant (Michael and Tari Taylor) of and from any and all past, present or future claims, demands, obligations, actions, causes of action, rights, damages, costs, loss of service, expenses and compensation which the plaintiff (Lisa Knight) now has, or which may hereafter accrue or otherwise be acquired by plaintiff, on account of the physical altercation.” Lisa signed the document, and her son’s case against Adam was “exceptionally cleared.”

In early December 2007, Taylor was involved in another police matter – an apparent high school hazing ritual. According to a Sheriff’s Office report, Taylor, his younger brother and another student accosted a fellow wrestler who was on crutches, carried him into the wrestling room and held him down while Adam Taylor took his pants down and “rubbed his balls” in the boy’s face. Reports indicated that the younger Taylor filmed the incident, which was later posted on YouTube.

The victim’s family reported the incident to the school. Because hazing is a felony in Florida, the school’s resource officer began an investigation. Each member of the wrestling team submitted to an interview, except the Taylor brothers, who invoked their right to an attorney.

Folio Weekly interviewed Mike Taylor for a story about the incident (“Hazing High,” Dec. 11, 2007). He described the incident as an “initiation” that all freshman wrestlers go through. He added that Sheriff Beseler had “made a big deal” of it since he was challenging Beseler for sheriff and Adam was his son. (His noted that Adam “might be in line for the Olympics in wrestling,” and he did not want this incident to “hurt his chances.”)

Ultimately, the family of the victim chose not to press charges. Adam Taylor went to the home of the victim and apologized. The State Attorney’s Office again “exceptionally cleared” the case, and left the matter up to Clay County School Superintendent David Owens. He suspended the boys for a couple of weeks.

Both Samantha and Brooke say that seeing Adam Taylor after the attacks was humiliating and scary. Although Brooke had transferred to Orange Park High School, Adam’s then-girlfriend went there, too. Both girls played on the school’s volleyball team. According to Katherine Jones, he showed up at several of the games, boldly sitting in the bleachers mere feet from the Jones family.

“Each time my child looked into the bleachers at her family, she had to see Adam looking at her,” Katherine says with a loud exhale. “It was [as bad as] intentional torture.”

Katherine also says that after they reported the incident to police, she twice saw Taylor’s black Ford Explorer parked across the street from the family’s home – even though they live in a gated community with limited access. Katherine felt it was deliberate intimidation and reported it to the Sheriff’s Office. She was assured that Adam Taylor’s attorney would advise the teen to stay away from the home. However, Det. Sharman made no note of Katherine’s complaint in his report.

Samantha, too, felt intimidated. In May of this year, while the investigation was still underway, Samantha received a text message from her boyfriend’s phone while they were at school. “I want sex,” the message said.

Furious, Samantha immediately called her boyfriend. He told her that Adam Taylor had taken his phone and sent the text. He also said Adam told him he should convince Samantha to drop the charges.

When Daniel Cannon learned of the incident, he was livid. He contacted Julie Schlax, director of the State Attorney’s Office’s Special Assaults Unit and the prosecutor handling the case. Schlax said she would notify Taylor’s attorney. (There was no mention of the incident in the State Attorney’s case file.)

Approximately a week later, Schlax called Daniel. “It is with a heavy heart I tell you this,” Daniel recalls Schlax saying. “The State Attorney’s Office feels it would be better for your daughter not to pursue the case against Adam Taylor.” Schlax went on to say that her office had received a letter saying that Samantha had become quite promiscuous of late. Schlax acknowledged that she hadn’t talked to any specific boys to verify the claim, but added that she and State Attorney Harry Shorstein thought it best for Samantha to let the case drop.

Daniel vehemently disagreed. He told Schlax that the family wanted to pursue his daughter’s case, letter or no letter. And he noted that prosecutors hadn’t even bothered to check out the claims before deciding to drop the matter.

“I wanted to go forward,” Daniel told Folio Weekly. But prosecutors had made their decision. Says Daniel, “We weren’t even given a choice.”

The news that there would be no charges filed against Adam Taylor hit one of his victims especially hard. With the investigation against Adam ongoing, her parents say, she finally seemed to be recovering. But, in May, when the State Attorney’s Office dropped the case, she spiraled downward. In early June, she attempted suicide.

While the girl was still in the hospital, her therapist suggested she write Adam Taylor a letter. “I hate you,” the girl wrote. “I wish you were dead.”

Brooke is in therapy and spends a lot of time at her church. Her mother says she has become fixated on working out, trying to “be strong,” in case someone attempts to “hurt” her again. Daniel Cannon says his own daughter’s depression has worsened, and she’s exhibited some “extreme” problems. Samantha, who swears she was a virgin when the attack occurred, has nothing left of her once-youthful innocence. Her face, though quite pretty, lacks spirit. And while she once seemed years younger than her age, she now exhibits a wariness that makes her seem much older.

Both pairs of parents say they will fight to see Adam Taylor punished. But as the race for Clay County Sheriff heats up, they’ve found their motives increasingly dismissed as political. Mike Taylor’s supporters suggest that Beseler supporters started the “rumors” about Adam Taylor in order to discredit his dad. The families of the girls insist they have no link to Sheriff Beseler, but they admit that their anger and frustration has given them an interest in seeing Mike Taylor defeated.

The families also believe that politics played a role in the State Attorney’s decision not to prosecute. They note Harry Shorstein’s very public disputes with Sheriff Beseler as well as his close ties to former Sheriff Scott Lancaster, a staunch supporter of Mike Taylor. The families suggest that Shorstein’s office has a vested political interest in Taylor’s candidacy. In his letter to Gov. Crist, Daniel Cannon cites the families’ suspicion that “[State Attorney Harry] Shorstein’s decision not to prosecute this young man was the result of political persuasion.”

Katherine Jones says that while she doesn’t have any strong feelings about Beseler, she plans to campaign against Mike Taylor. “He should abandon his political efforts and focus his energies on seeking help for his deeply disturbed son,” she says. Daniel Cannon agrees. “I was never into politics,” he says. “But I am now. If a man can’t control his own son, how can he control hundreds of men?”

Susan Clark Armstrong Folio Weekly